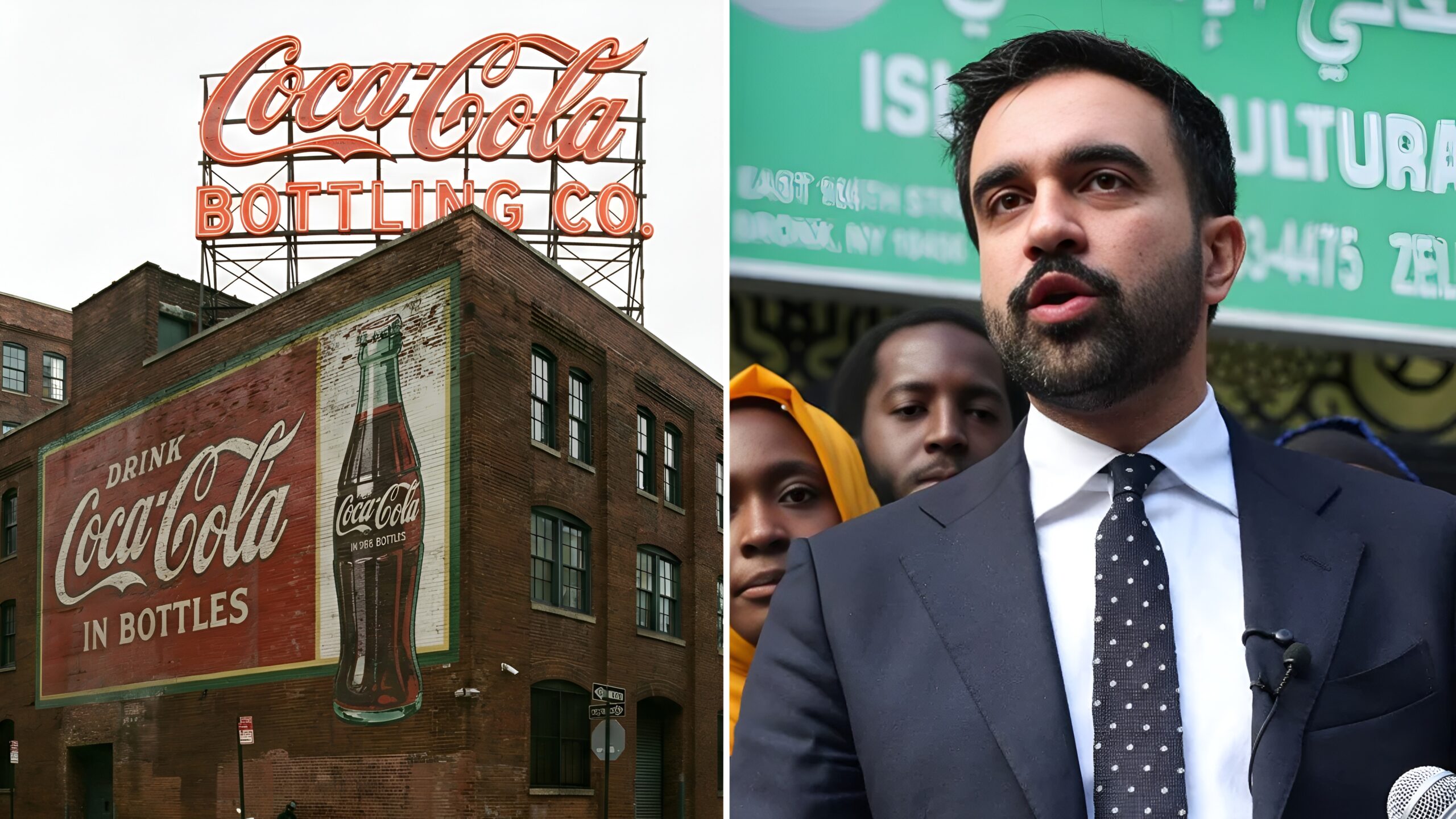

The news broke with a jolt that rippled across New York City: Coca-Cola would be closing its largest manufacturing facility in the city, a massive bottling plant that had operated for decades and employed hundreds. The announcement, arriving just days after Zohran Mamdani’s election as mayor, sent shockwaves through political circles, business groups, and—most painfully—through the factory’s workforce.

What stunned most observers wasn’t just the closure itself, but the speed at which it happened. There had been no public hints, no drawn-out negotiations, no advance signals suggesting the company was preparing to pull back from the city. Instead, a single corporate statement appeared early in the morning, confirming that operations would cease “in the near term” due to what the company described as “an evolving economic climate and shifting municipal priorities.”

Within hours, the political interpretations began. Supporters of outgoing leadership called the move a reactionary overcorrection by a company unwilling to adapt to a changing city. Mamdani’s critics framed it as an early warning sign—a sign that the new administration’s stance toward corporations might be driving major employers away.

Still, beyond the political drama, the closure landed hardest on the people who had built their lives around the factory’s rhythm.

For nearly forty years, the Coca-Cola plant had been an anchor in the neighborhood, its trucks rolling in and out from dawn until late into the night. For immigrant families who settled in Queens, jobs at the plant were a dependable source of upward mobility.

The work was steady, the union strong, and the pay predictable in a city notorious for cost fluctuations. Many workers stayed for decades, becoming experts in the intricate dance of assembly lines and machinery that kept the plant alive.

Now, those same workers gathered outside the gates in disbelief. Some held their badges loosely in their hands, unsure whether they were supposed to turn them in. Others paced in tight circles, their expressions a mix of anger and confusion. One employee, who had been at the plant since her early twenties, whispered to a coworker, “It feels like the end of an era nobody was ready for.”

The company’s explanation focused broadly on operational challenges—rising costs, uncertain regulatory changes, and what executives called “the city’s shifting policy environment.” They emphasized that the decision was about “long-term sustainability,” not politics. But few seemed convinced that timing played no role.

Mayor-elect Mamdani addressed the situation from City Hall’s briefing room, acknowledging the “deep personal and economic consequences” of the closure. He urged Coca-Cola to work with the city to provide transition assistance for affected workers and framed the situation as a test of how New York responds when corporate decisions collide with community interests.

“The people who kept that factory running deserve more than a press release,” he said. “They deserve a plan.”

Local unions echoed that sentiment even more forcefully. They accused the company of abandoning its workforce, and some leaders argued that the closure had been quietly in the works long before the election. To them, pinning the decision on shifting city priorities was simply a way to avoid scrutiny. They pointed to other states where Coca-Cola had consolidated operations, arguing that the company’s long-term strategy had already been moving toward fewer, larger regional hubs.

But regardless of the company’s intentions, the immediate impact was undeniable.

In the surrounding neighborhood, small businesses began bracing for a steep decline in foot traffic. The deli across the street, where workers bought breakfast sandwiches by the dozen every morning, suddenly faced an uncertain future. The owner shook his head as he restocked the shelves, saying, “When the factory slows down, this whole area feels it. When it shuts down, it’s like someone flipped a switch.”

Economists weighed in with mixed assessments. Some viewed the closure as part of a larger trend: big manufacturers exiting high-cost cities in favor of cheaper regions. Others argued that companies sometimes use political transitions as convenient justification for decisions made for purely financial reasons. Still others cautioned that the move might represent the beginning of a new tension between New York’s evolving political structure and the corporations that help fuel its economy.

What remained unmistakable was the emotional toll on the workers themselves. Many described feeling blindsided. The factory had recently completed a round of equipment maintenance, and shifts had been running normally just days before the announcement. Some employees had even been discussing holiday overtime opportunities.

In the days that followed, community organizations set up meetings to help workers understand their severance packages and begin the search for new employment. Local nonprofits focused on job training offered their assistance, though many workers wondered whether new training would help them compete in an increasingly automated labor market.

The city government also signaled its intention to step in, with Mamdani’s transition team proposing the establishment of a rapid-response group to support displaced workers. Early ideas included retraining programs, relocation assistance, and exploring whether another company might be interested in taking over the facility. Still, even those plans could not soften the shock of the initial announcement.

Rumors swirled about what would happen to the sprawling property—some speculated it might be converted into a distribution center, while others imagined the site being redeveloped into housing or turned into a mixed-use space. No clear plan emerged, only more questions.

The broader debate over the city’s future intensified as well. Supporters of the new mayor argued that New York should not be held hostage by the preferences of multinational corporations. They insisted that long-term stability required investment in workers, not appeasement of corporate pressure. Critics countered that the city’s aggressive political shift might alienate businesses that contribute significantly to the tax base and local economy.

Both sides agreed on one point: the closure had become more than a corporate decision. It had become a symbol.

In the weeks ahead, the city would wrestle with how to respond—not just to the practical challenges of job loss, but to the narrative shaping around it. Was this closure an unfortunate coincidence? A calculated corporate move? A reaction to political change? Or some blend of all three?

For now, the factory stands quieter than it has in decades. The clatter of machinery, the whistle signaling shift changes, the constant flow of trucks—all silenced. Workers pass by the gates, still half expecting to hear the usual hum of activity.

Instead, the silence lingers, heavy and unresolved, marking the beginning of a difficult chapter for hundreds of families—and raising questions New York City will be forced to confront in the months ahead.